Winter Greens

- Clifford Brock

- Dec 7, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2023

First off, this post isn't about our edible greens like turnip greens and collards. This is about southern bulbs and tubers that do most of their growing in the cool months. I'm particularly interested in learning how to differentiate different bulbs solely by their foliage.

One of the wonderful things about horticulture is the ever-changing nature of our landscapes. I love walking around and noticing all the subtle transformations, even now in mid-December. Despite our common belief, winter isn't static and many of our plants are actively preparing or even growing. But why would a plant evolve a strategy to grow in the winter considering all the perils and hostile conditions nature can offer?

We must first think of their native environment, or where did they evolve? Many of these plants come from subtropical or Mediterranean zones of temperate climates. Therefore, they aren't adapted to extended periods of extreme cold. While most can tolerate air temperatures into the 20s, when it gets down in the teens, their cold defenses are obliterated and the foliage is killed. But each plant has its unique limit, for example, within the spider lilies (genus Lycoris) some species are more cold-hardy than others (it even varies within cultivars!). So you can't extrapolate that just because it is the same species, it can tolerate the same level of cold... it just depends on evolutionary origins or the nature of the man-made hybrid.

Another reason temperate plants probably evolved winter growth is to escape the harsh conditions of the high summer. Most species, even ones that bloom and grow during the hot months, take a sort of break from activity when night-time temperatures approach the higher 70s. As research indicates, nighttime temperatures seem to play a larger role in whether a plant makes it or dwindles away. So in many ways, heat plays an equal role with cold in the success of growing bulbs in our climate.

As climate change continues and accelerates, many of our beloved historic and native perennials will no longer thrive in our future climate. But just as one door closes, new species will fill the gap, and many of these species will be winter-green species.

We are already familiar with many of these winter-growth bulbs. Plants like Lycoris (spider lilies, Red Schoolhouse Lilies (Rhodophiala), and many species of Narcissus are among the countless horticultural species that produce winter foliage.

One plant primarily grown for its winter foliage is the beautifully mottled Arum italicum. While it is native to the Middle East and Mediterranean, arum lily thrives here in the southeast and can even escape and naturalize into woodland settings.

Ipheions, or Spring Star Flowers, are another southern heirloom that do all their growing in the winter and then bloom in the early spring. They make great low-growing ephemerals that can coexist with grass without being much of an issue. This is because most of us aren't mowing during the cool season. In Madison, GA you can see many examples of "Ipheion lawns" around the historic homes. However, with the increasing use of herbicides, fewer and fewer of these mass plantings persist.

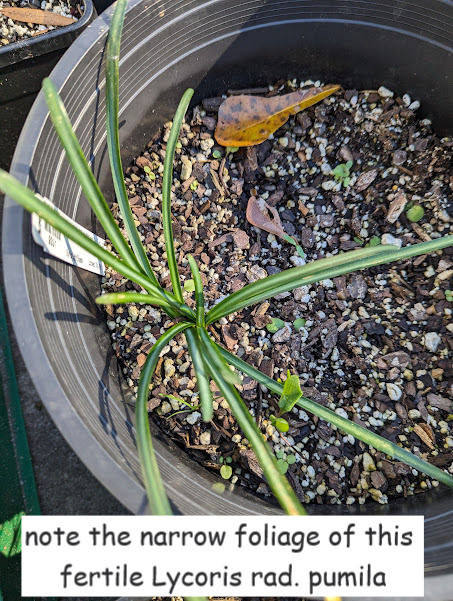

As you become a more experienced gardener, you will begin to notice subtle differences between the leaves of different bulbs. You'll notice, for example, that yellow spider lilies have really wide leaves when compared to their red cousins. You'll also be able to distinguish between cultivars based on bloom time and the emergence of their foliage. This is a particularly useful skill, as most bulbs only flower for a few short weeks while are "in foliage" for much longer!

It just occurred to me that another likely reason any temperate plant may want to grow in the winter is to benefit from the deciduous nature of many of our trees. In other words, many of our shade trees, like oaks and maples, are deciduous (no leaves in winter) and therefore small understory plants that can photosynthesize during that period may gain an advantage. But it is also true that the length of day and intensity of sunlight is diminished in the winter, so I'm not sure how this is a factor.

Regardless of the reason, I'm thankful that we live in a climate that is hospitable for winter-growing species. It eases some of the bleakness and otherwise "sterile" feeling winter evokes.

Comments